A recent article published on Quartz, titled “Get a PhD – but leave academia as soon as you graduate” has been doing the rounds on twitter. There were a few things that irked me about the piece, despite its seemingly glowing account of undertaking a research degree.

The gist of the article is this: doing a PhD is a terrible financial decision, but worth doing anyway.

On one hand, the article is a positive, bordering on gushing, account of the post-graduate experience. It’s a defence against economic rationalism in higher education, and a reaffirmation of the transferability of research skills into non-academic work contexts. I agree with all of this, and think these messages should be more widely heard; especially by those who are on the fence about starting a PhD themselves, and even more so (I suspect) by those who have just started. These are a particularly fragile bunch, and ‘stories from the other side’ are vital in keeping motivation and momentum in the early stages of your candidature.

On the other hand, the article acts as a warning against the financial pitfalls of PhD programs, mainly through painting a bleak picture of the academic job market for new graduates. Importantly, it also has a few hidden barbs that are not expanded upon, but which would be key considerations for anyone even contemplating a PhD. The two biggest are in this sentence (emphasis mine):

“After nearly 10 years in graduate school and substantial debt you still end up a part-time or adjunct professor (and still in debt).”

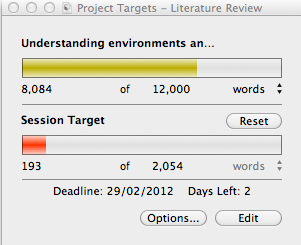

It is these points that I took issue with, primarily because I assume they speak solely to a North American context. I don’t intend this to be a value judgement on conducting a PhD in one country over another; it is simply worth noting though that, in Australia, the UK and elsewhere, the experience of a PhD is very different. Most PhDs are completed within 3 – 4 years in these countries, and in Australia anyway, most are funded by scholarships that are modest at best, but are tax-free. There are no fees associated with the degree, and you are allowed to work up to 10 hours a week on the scholarship, which I did for the first two years of my candidature. It’s certainly true that most people could still earn more money elsewhere, but doing a PhD will hardly “ruin your life”, as the author claims.

I understand that it is not the point of the article to warn off people against starting a PhD. By listing a number of statistics that highlight just how unlikely it is that you’ll come out on top, financially, it’s actually saying that it’s worth it anyway. I wanted to point out, though, that in Australia and other countries around the world, the financial cost of a PhD is significantly less. Indeed, here in Australia, a few of my colleagues started studying PhDs because the job market was so bad at the time (circa-GFC). In these cases, a research degree was a viable-enough alternative to a commercial job, especially for those coming directly out of their undergraduate studies.

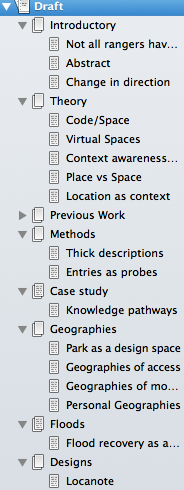

Whilst the article is, on the surface of things, positive of the PhD experience, it does go to efforts to paint a picture of ‘the noble researcher’ who has chosen to forego the status-quo of the job market in order to engage in a journey of self-fulfilment. This is a dangerous message to send: in doing so, it ignores the actual labour of a research degree (and the value that labour produces).

Research should not be considered a noble pursuit that sits outside the realm of your more run-of-the-mill capital production. Those taking it on should definitely be doing it for the right personal reasons, but they also deserve recognition that their research is a form of work that is valuable in and of itself. It should be rewarded as such, no matter which path they go down afterwards.