This week I finally received my ethics approval. For those who haven’t had to deal with an university ethics committee before, it’s a notoriously lengthy and tedious process. I managed to have my research methods approved within 3 months, which is about half the time it took my research partner – so understandably, I’m pretty happy!

As part of the ethics submission I essentially planned out every stage of the hands-on research I’ll be conducting with park rangers. I’m relying heavily on qualitative methods to uncover the behaviour, goals and habits of park rangers as they go about their jobs – focusing on who they communicate with, what information they impart and use, what decisions they make, and how all of this related to their notion of location. Essentially, I’m treating park rangers as a community with their own set of practices, and, through qualitative research, am hoping to uncover deeper links between themselves and the spaces they manage.

Thick description

A key aspect of almost all qualitative research is the notion of “thick description” – a term that appears in just about every text book on the subject. However despite it’s seeming importance, it’s a notoriously difficult concept to define. There have been numerous attempts, as documented in Joseph Ponterotto’s paper from 2006 (reference below).

In 1973, Geertz was the first to use the term in relation to qualitative research, and states the following:

From one point of view, that of the textbook, doing ethnography is establishing rapport, selecting informants, transcribing texts, taking genealogies, mapping fields, keeping a diary, and so on. But it is not these things, techniques and received procedures that define the enterprise. What defines it is the kind of intellectual effort it is: an elaborate venture in, to borrow a notion from Gilbert Ryle, “thick description”.

Denzin (1989) attempts to define thick description by comparing it to “thin description”. According to Denzin, thick description has the following features:

“(1) It gives the context of an act; (2) it states the intentions and meanings that organize the action; (3) it traces the evolution and development of the act; (4) it presents the action as a text that can then be interpreted. A thin description simply reports facts, independent of intentions or the circumstances that surround an action. (p. 33)”

Other definitions essentially equate it to doing ethnography – in that, the actual nature of ethnography is to gather thick descriptions. This is the most common link between the definitions – essentially, like ethnography as a practice, “thick description” can be said to provide context and meaning to observed actions, rather than simply recording the occurrence of an event in isolation. It’s more about recording the story of a fact, rather than the fact itself.

There are a number of ways to achieve the type of data that might be defined as “thick” – participant interviews, field observations, analysis of personal spaces and artifacts, and more. Diary studies are another well documented form, as part of a broader notion of a “cultural probe”. This is one which I intend to use with park rangers.

There’s an app for that

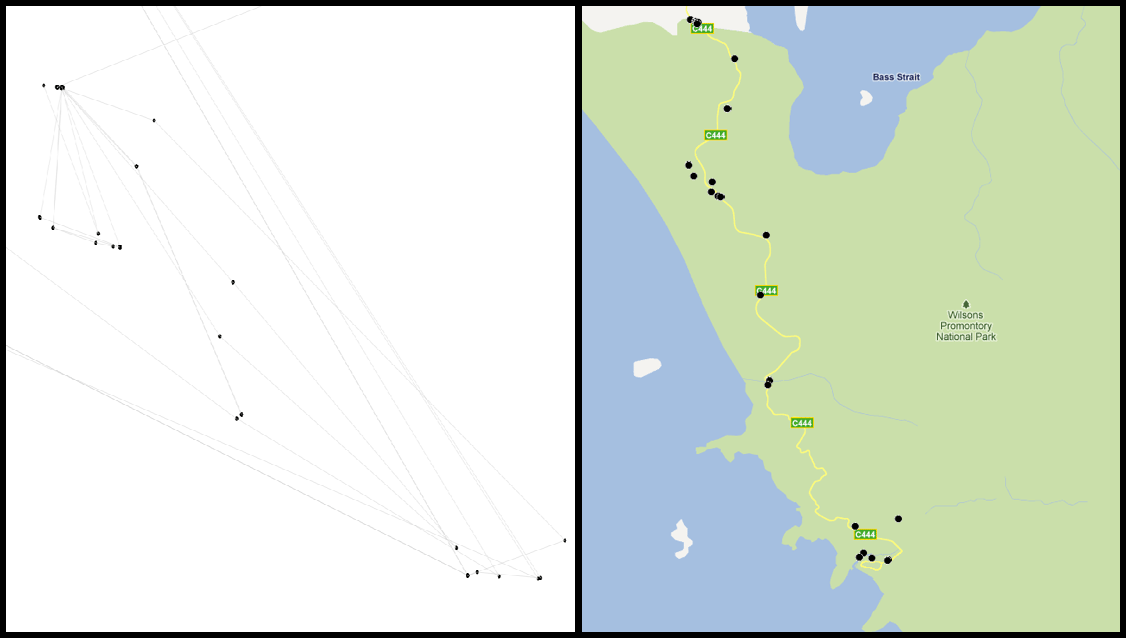

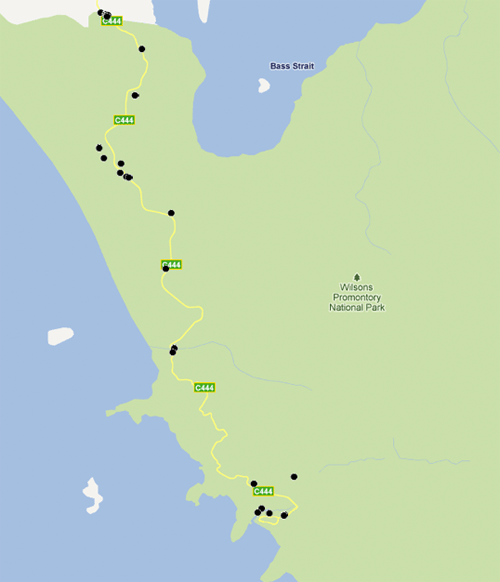

To this end, and given the extra-special role that location plays in my research, Reuben and I have built a custom application for park rangers, that asks them to provide thick descriptions of the locations they manage.

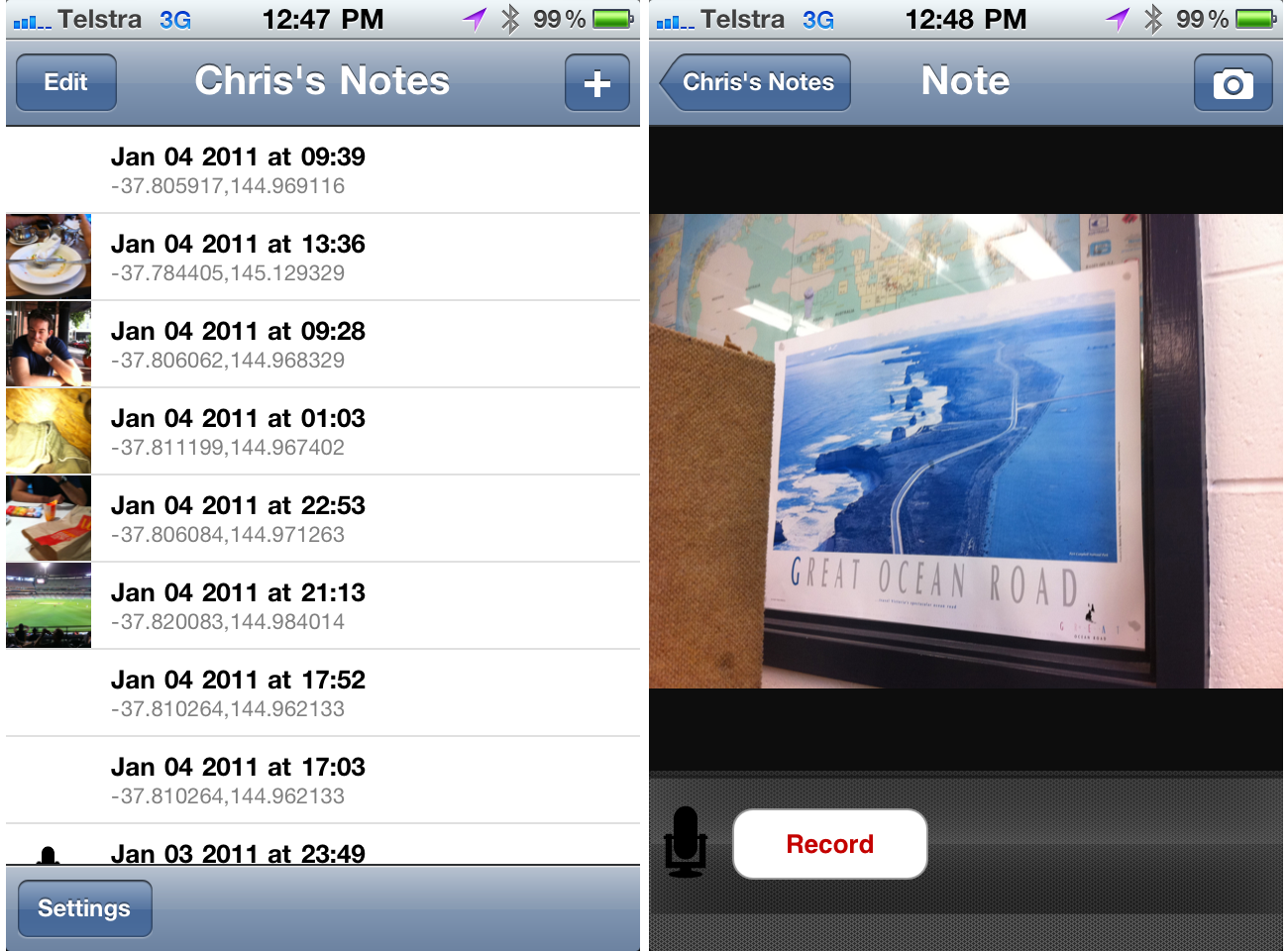

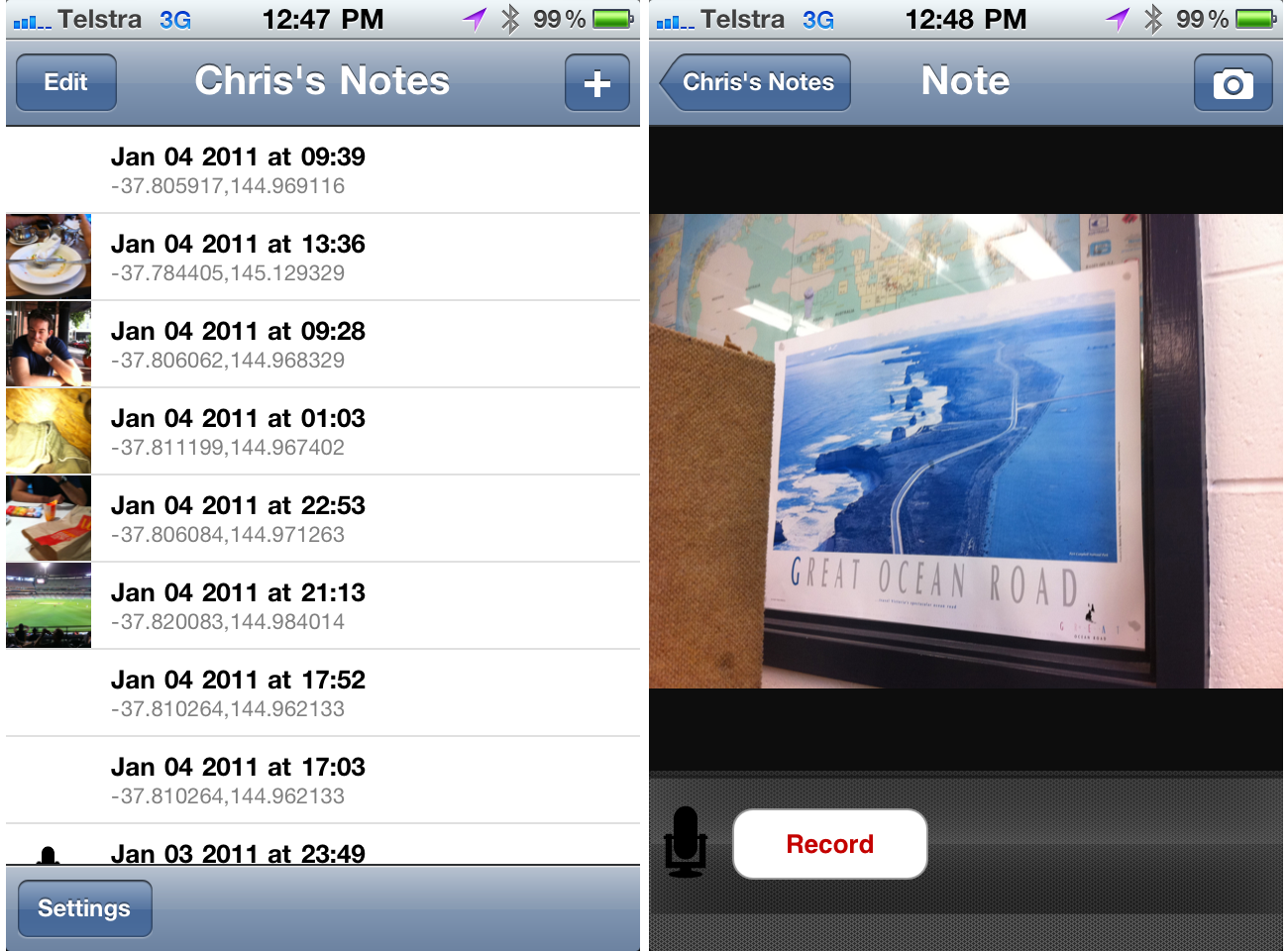

The application is mobile based (iOS specifically), and relies on a combination of GPS, photography and audio descriptions to gain a subjective sense of the spaces and places rangers make decisions about.

Each entry into this diary app is time-stamped and can be any combination of coordinate, photo and audio description. It’s this combination of audio and visual input that is the most powerful – given the nature of a park rangers job, audio descriptions are the most effective means of capturing the actions of rangers, and one that matches their current behaviour more closely than text based descriptions.

The goal is to create a low barrier to entry for rangers wanting to talk about their jobs as they’re doing them. Rangers will then be allowed to self-categorise/tag entries ex situ, before being visualised and used as discussion points in follow-up interviews.

The above screenshots are from the first functional version of the app, with many more improvements (particular design) to come.

Focusing the diary

To help guide the use of this application, we’re providing rangers with a set of guidelines on what types of information and input we’re interested in. Broadly, we’d like them to capture their interactions with other rangers, the decisions they make, the information they use in making these decisions. Given the role of location in all of these research questions, their entries will be analysed and visualised on maps to allow them to comment on the relationship between themselves and their environment.

We want to make this a fun activity for rangers, and we’ll be conducting kick-off sessions, and I will be following rangers into the field regularly to make my own observations and hopefully help overcome any confusion about the study before rangers are left alone with the application.

Wrap up

Thick description is a key part of the qualitative research I will be conducting with rangers at Wilson’s Promontory national park – I hope to uncover deep relationships between the rangers themselves and the locations they manage. As part of a much wider research program, we’ve designed and implemented a location-based diary study tool that will allow us to conduct remote research to be used as probes for further interviews.

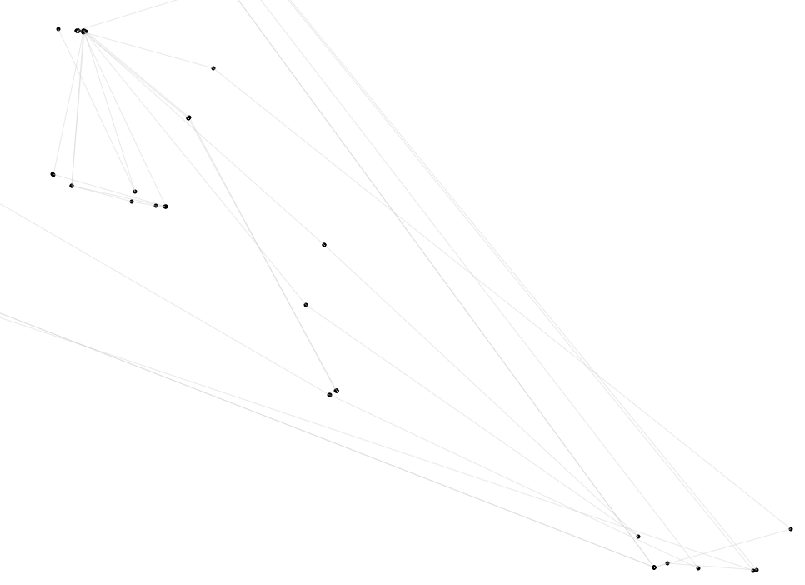

Next for us is to build a visualisation interface for all this data – one that will allow us as researchers a way of making sense of qualitative data about locations, but one that will hopefully provide the basis of a knowledge management tool for Parks Victoria themselves.

References

Please note that the links below are to purchase the references I use in this post on Amazon. If you do find them interesting and decide to purchase them, I collect a small commission. Doing so will help support this blog (and my research!) in a small way, and I will be very grateful!