This week I went to a seminar that focused on communicating research. It was a pre-requisite for entering the 3-minute thesis competition, which seems like a mini-TED for research students with a time limit. I don’t know if I’ll enter the competition (although there’s some impressive cash amounts up for grabs), but I’ll definitely be using some lessons from the seminar in my writing. The main thing I took away from it was the importance of having a story around the research, and allowing people to feel an emotional connection to it. This post is my attempt to add that story.

The story of National Parks

People love national parks – they are places families go, where summers are spent, and where kids grow up. They provide an escape from architected office buildings, armpits on crowded trains and suburban peak hour traffic. The air is fresh, and the landscape is rejuvenating.

When such a place is ravaged by fire, those that have developed a connection to it feel violated – it’s as if their house has been burgled. An uninvited stranger crashes through, sweeping away the things they feel that connection with and leaving a shell. Like being burgled, it’s not just the memory of absent things that lingers – it’s the thought that the once unquestionably secure destination is no longer so. We never feel completely at home again.

On top of this, fire is devastating for the ecology of a park. When controlled, it is a necessary part of managing the landscape. When unplanned, it can permanently damage the land and the lives of the creatures that inhabit it.

It’s important that we do all we can to manage the risks of unplanned fire.

Some rangers live in the city, and not all of them have beards.

Luckily, there are people whose job it is to do this. Parks rangers are often based in the same park for many years, and over this time they learn to recognise signs in the environment that warn them that a fire may get beyond control. They have sensors that tell them about fuel levels and soil moisture, but, like most of us, they also rely on their instinct, or their tacit knowledge.

At the same time, back in the city, there are people who don’t wear khaki shorts who play just as important a role in the park. These people keep track of ecological research about parks, plan studies to discover populations of rodents, and keep tabs on the regrowth of native scrub. They also coordinate external groups of volunteers and researchers who contribute information back to the organisation, and provide those “on the ground” with the data they need to make decisions.

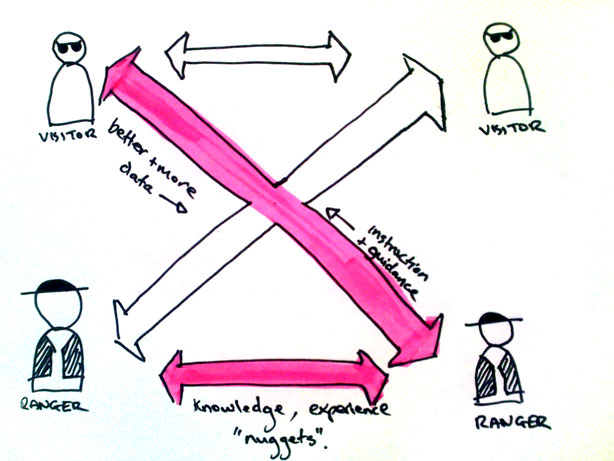

Both types of park ranger contribute to keeping the ecological balance necessary for healthy parks, and healthy people. However, both are struggling under the sheer weight of data available to them. Relevant scientific studies get lost in filing cabinets, and even when they are accessible they are not easily integrated into management plans. Similarly, rich, tacit knowledge is not accessible to other staff, and is lost completely when rangers retire or move on.

So on one hand, they need help dealing with the sheer quantity of data available to them. On the other, there’s a need to capture the rich, experiential knowledge that can help bridge the gap between the numbers, the park and the people in it.

A consensus of interpretation

The one common element to all of this data, information and knowledge is location. Reports are about regions in a park, rangers visit specific points and extrapolate their assessment to broader areas, and remote sensors are scattered in the park, forming a virtual topography of data on top of the natural environment.

Given the located and situated aspect of park management, it makes sense to give rangers tools to view information through the lens of location. It makes even more sense to give them tools through which they can record, interpret and use information about these places in the places themselves.

There are bodies of research that indicate that information makes more sense to us, and is more useful, when presented in the same context in which it is to be used. Facilitating the exploration of information in the places they are about can lead to the generation of better quality understandings of this information.

Similarly, we want to allow rangers to add their own meaning on top of this raw information, and to share and evolve that with other rangers. There’s also research, and indeed entire disciplines, that focus on computer supported collaborative work and show that the shared interpretation of data leads to better outcomes.

In the cloud

What this research plans to do is allow rangers to explore and interpret data about places, through mobile technology, in those very same places. Similarly, we want to allow rangers to share their interpretations of data with other rangers. By interacting with information and each other through mobile technology, rangers will ultimately form a human filtered and rich-in-quality body of knowledge that lives “in the clouds” above parks.

By giving rangers better access to the most important knowledge about parks, and particularly knowledge around fire management, they will be better equipped to manage and prevent unplanned fires. Uninterrupted, families can continue to form memories tinged with green, native flora and fauna can continue to flourish, and rangers can continue living in the country or in the city and with full freedom of choice around facial hair.

/eom

Well, that’s my first shot at adding some kind of narrative around what I’m doing. I’m in the process of applying to a doctoral consortium, and think this will really help me add context and reason to the more academic details. Thanks Inger!